An Interview with Peter Reginato

Peter Reginato’s upcoming solo exhibition, Chroma, opens on May 9, 2025, at the Sianti Gallery in Athens, Greece. This exhibition serves as the backdrop for a dialogue between Reginato, the renowned American abstract sculptor and painter, and Dr. Wei Wei, an art history scholar and abstract artist. Their conversation explores Reginato’s artistic journey, from the selection of paintings for the show to his early experiences in sculpture, offering an insightful case study on the methodologies and philosophical reflections that shape contemporary art practice.

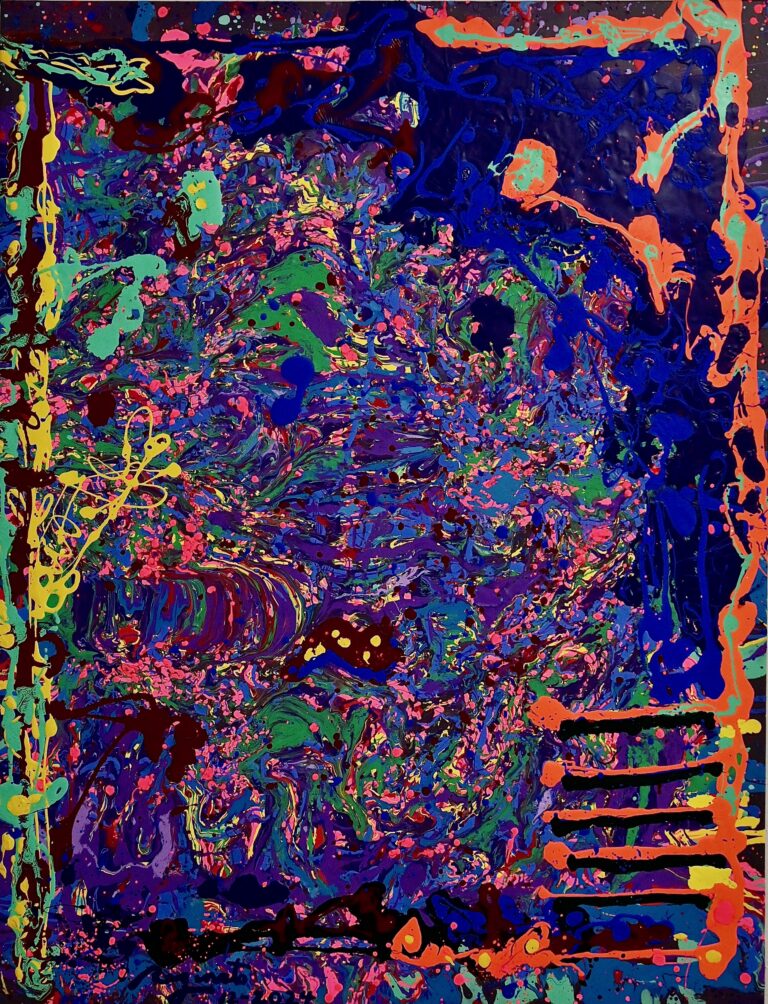

This conversation focuses on the paintings featured in Reginato’s upcoming exhibition Chroma and explores how Reginato’s artistry seamlessly navigates between two-dimensional and three-dimensional realms, evoking a poetic and enigmatic sense of transcendence.

The paintings in the exhibition can be understood as an interplay between Cubism and Abstract Expressionism, synthesizing elements of both movements in an innovative and personal way. Reginato’s approach to form and composition reflects the structured principles of Cubism, while his expressive, gestural handling of paint resonates with the energy of Abstract Expressionism. The works presented in the exhibition embody a continuation of those traditions, marking both a fusion and an evolution of these influential artistic languages.

Wei Wei, PhD (WW): To begin, could you introduce the combo paintings you will be presenting at the Chroma exhibition in Athens? What guided your selection process, and how do these works come together to tell a unique story?

Peter Reginato (PR): It’s a kind of combination of a Cubist story — a bit of Cubism mixed with Abstract Expressionism. And, of course, there’s also the Color Field school with its emphasis on color. I mean, that could apply in many ways, but the key idea here is the interplay between color and drawing. This particular group of works consists of about thirty paintings, including four large ones, approximately eleven feet wide and eight to nine feet high.

They’re pretty Cubist, but not in Picasso’s 1911 style. It’s a later style — what’s known as Synthetic Cubism. I often refer to it as Checkerboard Cubism. The way it’s divided, usually there’s a line running down the middle. One square is red, then the next is black, alternating back and forth. It’s not quite that rigid or simple, but it definitely carries the idea of a line that splits it — sort of like Mondrian.

WW: Modern art history, whether from the American experiment or the European side, is an orderly process. Your work clearly carries a unique voice. Could you please elaborate on how you developed your own artistic language?

PR: Of course. In my opinion, evolution is necessary. Some people were slightly upset when I transitioned into this new work because they were so attached to my previous pieces. But as an artist, you can’t just stay in the same place. You’ve got to keep moving forward, and that’s what happens to me now.

WW: As an avant-garde artist, you’ve always been at the forefront of your creative practice, leading the way in your genre. How do you continuously develop and push your work forward?

PR: I liked, and still do like, the development. Fernand Léger (1881—1995)—he’s great. I particularly love his early Contrast of Forms series. Those works, created between roughly 1912 and 1914, are incredible. But what’s interesting is that he only made about 12 or 14 of them. Why didn’t he make more? Now, I understand. After doing 10 or 15 paintings (in a certain style), you reach a point where it’s enough — you have to move on. Repeating the same motif might be comfortable, but real growth comes from change.

WW: I appreciate your use of the word “motif.” Could you please share more about how you navigate with motifs in your work? How do you find the balance between repetition and evolution?

PR: Actually, when I paint, I find that I can’t just repeat the same thing — it naturally varies. Somehow, it changes on its own, so I always end up doing something slightly different. Usually, it happens before I create the last painting in one series. Before I paint the final piece, I see something I did, then I want to follow up on it more. That discovery pushes me to expand on that aspect in the next phase of my work. I want to explore it deeply.

WW: So, let’s go from general to specific. Does your inspiration come from observing the world—the abstracted human figures or geometric forms of Manhattan’s skyscrapers? Are there any artists or artworks that you particularly look to when working or you have been attracted to? How have these influences shaped your approach to composition and space in painting?

PR: Mostly, it emerges from the paintings themselves, such as when I created the group with a vertical column type. Usually, when the first one I did was somewhat vertical, by the time I got to the third, it had a strongly dominant vertical composition. They may not be literal figures—though vertical columns can look like figures—but they, going vertically across the canvas, were very attractive to me.

Of course, there were other artists who explored verticality, such as Wifredo Lam (1902—1982), who sought to portray and revive the enduring Afro-Cuban spirit and culture. His work blends figures and abstract structures with his national influences.

One of the paintings I really liked was Easter and the Totem (1953) by Jackson Pollock (1912—1956). It’s very different from his “all-over composition” paintings, but the vertical movement fascinated me. Pollock made a significant shift with that piece. Actually, Pollock’s pouring and dripping paintings unsettled many people. But to me, those paintings felt like a glimpse into the future of painting and drawing.

Another work that resonated with me was Henri Matisse’s (1869—1954) Piano Lesson (1916). When I’ve seen others’ art that I’m attracted to, some kind of vertical composition, it made me think, well, stop screwing around with the other stuff and just start making them more vertical. So, those works made me rethink my own approach to verticality — not just in terms of orientation but in how space is structured within the painting itself.

WW: Pollock’s work is often characterized by its “all-over composition,” where no single focal point dominates the canvas, while your work maintains a structured foundation. Your approach is clearly distinct, yet I’ve noticed certain technical connections — pigments pouring and dripping. Are there some parallels in your work with that of Pollock, and how did you forge your own artistic path?

PR: I’ve kind of stayed away from the “all-over” look. By the time I was working with abstraction, a decade had passed since Pollock’s breakthrough. The “all-over” approach had become too widely imitated in the following decades. I mean, it was fascinating at first, but eventually, after several decades, it became predictable, almost a cliché. The Minimalists, the Color Field painters, even the Lyrical Abstractionists—they all resolved their compositions in that way. That’s great. However, I have no intention of dealing with it in the same manner. My paintings might echo some of those gestural techniques, but by pursuing subtle layers or spaces on canvases, even more than sculptures in three dimensions. They bring me joy.

WW: That leads us to a broader question — since the 1960s, you have dedicated many decades to abstract sculpture. But after 2000, your creative focus shifted more towards painting. What prompted this transition?

PR: In fact, I was a painter first before I became a sculptor. My first one-man show was in January 1966 in Berkeley, California. In the show, there were mostly paintings, alongside a few small sculptures. But I could already sense, even then, that I was moving towards sculpture.

WW: Could you delve into the specifics of your painting techniques, particularly regarding composition, structure, the interplay of color, and layers of pigment, and share insights from your own practical experience?

PR: I do look at certain of my own paintings for guidance—just to give me a little hint of where I want to go next. It could be in terms of color, or composition, or drawing, or even just figuring out how to get started on a new series. But at some point, the painting itself tells me what to do.

WW: You’ve spoken about following some sense of intuition in your painting process, allowing the work itself to guide you rather than adhering to traditional rules, like the avoidance of figure-ground relationships. How do you navigate the balance between spontaneity and structure in your compositions, and how has this approach evolved over time?

PR: Take the newest one, for example—the blue painting on the floor right now. It’s still wet. I laid down what you might call a ground, which has been key to my approach. In abstract art, there’s this long-standing rule—a big no-no, actually—that you shouldn’t have a figure- ground relationship. Well, I say screw that. I can do so much more than just make patterns. That’s where so many artists seem stuck.

One of the reasons I started painting was that I felt it was time for painting to break out of the box it had been placed in—regardless of the artist, the style, or the category. Abstract painters, for example, have been so bound by the New York School Ab-Ex Color Field and Minimal rules.

I thought, why not push beyond that? Why not break away from those conventions? Not that I’ve broken them enough, but I wanted to move beyond certain ways of working that felt limiting. So I thought, Why not draw? Why not draw directly into the painting?

Back in 2015, I created a group of large paintings—about five or six of them. They were successful. One of them, though, I never stretched because, at the time, I felt it was too derivative. So, I rolled it up, thinking, I don’t know about this one. But looking at it now, I realize I was crazy—it wasn’t derivative at all. It was all me. The color was incredible, and one of these days, I’ll stretch it. I still have three or four of those pieces from that period.

WW: I know you also do many drawings on paper. Could you talk about your paintings and drawings? How do you see the role of drawing in your practice today? Does it serve as a foundation for your paintings, or has it taken on a different purpose?

PR: So I continued painting and drawing—especially the colorful drawings. There’s definitely a relationship between them, though not a direct one-to-one connection. Instead, they reflect each other in a mutual way.

Right now, it’s challenging to balance making works on paper with large-scale canvases. There was a time when my drawings and paintings were deeply interconnected, but at the moment, I feel that relationship shifting. Still, the process continues to evolve.

WW: Looking ahead, how do you hope your work will be seen and experienced in the future? Do you think about the lasting impact of your paintings, and what do you hope people take away from them?

PR: In the future, when someone looks at my work, I believe they will get something out of it, and people will still see as much as they find them now. I really hope people could get some kind of pleasure, Fauvist color, lines that truly stand, or the process of evolution.

In the Athens show, there are small paintings that connect to an earlier series—works that carried a kind of excitement, something I wanted to explore further. When I look at my own paintings, I ask myself: What do I really like about them? What do they take with me to the next painting?

Some people say, Your works make us smile or feel joy. But I don’t really paint for that; I paint what I have to paint. I am just painting. It’s a kind of pleasure to keep innovating.

WW: As the local audiences step into your exhibition, could you please share a few words to guide them as they view the show? Perhaps some thoughts or reflections?

PR: Just look at the paintings; spend time with them. Or maybe glance at them quickly, walk away, and then come back. That’s the unique thing about painting, unlike film, theater, or literature, where you have to engage over time to fully experience the work. But you can look at paintings for three seconds and form an impression, or you can stand before them for hours. Both approaches are effective, and the experience remains open-ended.

Peter Reginato’s work is a testament to continuous evolution, blending Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, and intuitive spontaneity. His refusal to conform to rigid artistic rules reflects a deep commitment to exploration and reinvention. Inspired by Léger, Pollock, Matisse, and Lam, he embraces both structure and freedom, allowing each painting to guide the next. His approach balances structure with fluidity and discipline with freedom.

Despite his technical and conceptual rigor, he leaves room for spontaneity. Reginato’s reflections on his own paintings — how they carry him forward, how they evolve over time—illustrate an artist who remains deeply engaged in his work.

Furthermore, from the perspective of viewing, it is delightful. Art isn’t about rushing to understand, and it’s about allowing the work to meet you where you are. Approach the paintings in your own way — there’s no single correct method.

Peter Reginato (b. 1945) was raised in Oakland, CA, and attended the San Francisco Art Institute on a scholarship from 1963 to 1966. After moving to NYC in 1966, he participated in two Whitney Biennials and has received honors including a Guggenheim Fellowship, a NEA grant, and three Pollock-Krasner Grants. He has had nearly 70 solo exhibitions.

Selection of stories, guides, and more from the League.